Luca Cambiaso (Moneglia (Genova),1527 - El Escorial 1585)

(Moneglia (Gênes), 1527 – El Escorial, 1585)

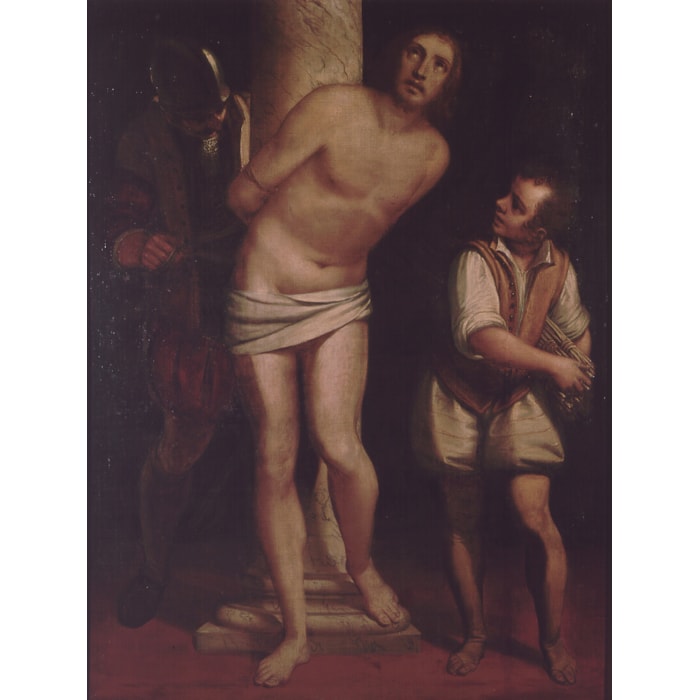

Le Christ dépouillé de ses vêtements par ses bourreauxHuile sur toile, 184 x 133 cm

- PROVENANCE

- BIBLIOGRAPHIE

- EXPOSITIONS

- DESCRIPTION

PROVENANCE

Gênes, collection de Giovanni Battista Villa (1824?-1900), le tableau se trouve dans son inventaire après décès (Casa Villa, 1900, n° 405) ; par descendance sa fille, Gênes, Collection de Mme Eugenia Villa veuve Ghisolfi jusqu’à la date de sa mort en 1952 (voir cat. exp. 1927) ; par descendance, Gênes (Coronata), collection de Mme Flora Livi Villa ; Monte Carlo, collection particulière

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

-Mario Labò, Mostra centenaria di Luca Cambiaso, cat. exp., Gênes, décembre 1927, p. 21, n° 22 ;

-Adolfo Venturi, Storia dell’Arte Italiana, vol. IX, parte VII, Milano, 1934, p. 853 ;

-Giuliano Frabetti–Anna Maria Gabbrielli, Luca Cambiaso e la sua fortuna, Caterina Marcenaro (dir.), cat. exp., Gênes, Palazzo dell’Accademia, juin – octobre 1956, n°51 ;

-Bertina Suida Manning-William Suida, Luca Cambiaso. La vita e le opere, Varese-Milan, 1958, p. 48-49, 105 ;

-Lauro Magnani, Luca Cambiaso da Genova all’Escorial, Gênes, 1995, p. 224, fig. 250, p. 227, note 26 ;

-Giulio Sommariva, in Luca Cambiaso. Un maestro del Cinquecento europeo, cat. exp., Gênes, Palazzo Ducale – Musei di Strada Nuova, 3 mars 2007 – 8 juillet 2007, p. 318, sous le n° 57 ;

-Anna Manzitti, in Luca Cambiaso. Un maestro del Cinquecento europeo, cat. exp., Gênes, Palazzo Ducale – Musei di Strada Nuova, 3 mars 2007 – 8 juillet 2007, p. 322, sous le n° 59, repr.

EXPOSITIONS

-Mostra centenaria di Luca Cambiaso, Gênes, 1927 ;

-Luca Cambiaso e la sua fortuna, Gênes, Palazzo dell’Accademia, juin – octobre 1956.

DESCRIPTION

Œuvre en rapport : Une autre version est publiée et reproduite par Suida Manning (1958, p. 413, fig. 417), alors dans la collection de l’avocat Attilio Caveri (1891-1976) de Moneglia.

Fils du peintre Giovanni Cambiaso (1495-1579), un artiste d’envergure plus modeste, Luca Cambiaso cultive dans cette seconde moitié du XVIe siècle, un langage artistique qui se dénote du maniérisme ambiant, son style évoluant en fonction d’apports variés qui vont de la clarté et de la monumentalité des figures de Michel-Ange (1475-1564) aux nouvelles solutions artistiques en provenance de Parme, en particulier pour la lumière, mises en œuvres par Correggio (c. 1489-1534) et Parmigianino (1503-1540).

Notre peintre développe ses nocturnes à partir de 1575, et ce, jusqu’en 1583, date de son départ pour Madrid où il travaillera à l’Escorial. Dans le domaine des scènes éclairés à la chandelle, Cambiaso fait figure de novateur, anticipant les résultats analogues obtenus par les caravagesques nordiques comme Gerrit van Honthorst (1590-1656) ou encore, le français Georges de la Tour (1593-1652).

Dans son œuvre, la section des nocturnes s’ouvre avec le chef-d’œuvre du Christ devant Caïphe (Gênes, Accademia Ligustica di Belle Arti, fig. 1), œuvre proche de notre tableau tant du point de vue du style que par ses dimensions imposantes.

Ici, la flamme de la chandelle éclaire d’une lumière blanche le visage calme et résigné du Christ ainsi que son buste afin d’accentuer l’effet dramatique, relayé par le visage du jeune enfant tourné vers ce dernier et portant, sous son bras droit, les verges pour la flagellation.

Au second plan, les figures des bourreaux, synonymes du mal, sont volontairement caricaturales. Leurs visages burinés aux expressions outrées, aux traits très marqués, se retrouvent, de même, en arrière-plan du Christ devant Caïphe.

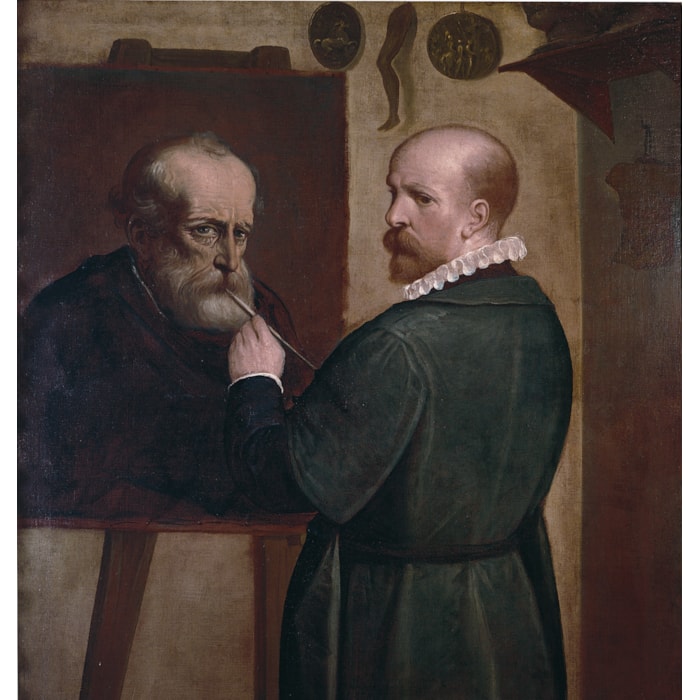

La scène représente le moment qui précède la flagellation, alors que l’un des bourreaux a déjà la corde enroulée autour de la main gauche et serrée entre ses dents, prêt à agir pour attacher le Christ à la colonne en marbre veinée. Suida Manning a émis l’hypothèse que la figure d’homme barbu qui émerge à gauche de la colonne et qui regarde le spectateur puisse être un portrait de l’artiste qui, en effet, était barbu comme on peut le voir sur L’Autoportrait avec le portrait de son père (Gênes, Palazzo Bianco, fig. 2) mais qui était aussi chauve et roux, ce qui n’est pas le cas du personnage sur notre tableau.

Quant au sujet du Christ dépouillé par ses bourreaux, Carlo Giuseppe Ratti mentionne avoir vu un tableau sur ce thème dans la dernière des six chapelles de l’Église du couvent de San Francesco di Castelletto (aujourd’hui détruite)1. Cependant il est difficile d’affirmer qu’il puisse s’agir de notre tableau car il existe une autre version dans une collection privée à Moneglia (voir « Œuvre en rapport »). Une variante du Christ à la colonne (Genova, Musei di Strada Nuova – Palazzo Bianco, fig. 3) ne présente, avec les figures du Christ et de l’enfant, que le seul soldat portant un casque occupé à lier les mains du Messie à la colonne.

Notre tableau vient tout naturellement s’insérer dans cette suite de tableaux nocturnes et monumentaux sur la vie du Christ et dialogue parfaitement avec Le Christ devant Caïphe de l’Accademia Ligustica de Gênes. Les nocturnes de l’artiste sont presque exclusivement des tableaux à sujets religieux tirés du Nouveau Testament, dont leur éclosion dans les années 1570 est, sans nul doute, liée au mouvement de la Contre-Réforme. Le style tardif de Cambiaso, ce que l’on a coutume d’appeler sa troisième période peut se résumer, au point de vue du style, par la formule évocatrice de Bertina Suida Manning : « une sérénité contemplative croissante et une simplicité monumentale »2, formule qui trouve écho dans la franche trilogie de Lauro Magnani : « Méditation, rigueur et simplicité »3. Le rôle de Cambiaso dans l’histoire du nocturne peint est fondamental car tout en reprenant cette tradition, déjà exploité par les artistes tant nordiques qu’italiens, il s’intéresse plus particulièrement aux différentes possibilités que lui offre l’ajout d’une lumière artificielle. Il s’agit là d’un apport d’une grande originalité et qui aura un réel impact sur la peinture caravagesque.

Notes :

1-Carlo Giuseppe Ratti, Istruzione di quanto può vedersi di più bello in Genova in Pittura, Scultura ed Architettura, Gênes, 1766, p. 227 ; Carlo Giuseppe Ratti, Istruzione di quanto può vedersi di più bello in Genova. Descrizione delle pitture, sculture e architetture ecc. che trovansi in alcune città, borghi, castelli delle due riviere dello Stato Ligure, 2 vol., Gênes, 1780, p. 251.

2-Bertina Suida Manning, « The nocturnes of Luca Cambiaso », The Art Quarterly, vol. XV, n° 3, 1952, p. 199.

3-Il s’agit du titre de l’un des derniers chapitres de la monographie de Lauro Magnani, Luca Cambiaso da Genova all’Escorial, Gênes, 1995, p. 211.